Australians who are concerned about the slowing Chinese economy may find some solace in the fact that Canberra is already frantically trying to hammer out a Free Trade Agreement with India, the second-most populous nation in the world.

There is every reason to expect that India will rank among Australia’s top trading partners if all goes according to plan. She has the potential to become Australia’s largest trading partner at this time, the “new China,” as it is known in some circles.

The declarations made by its federal ministers show how eager Australia is to provide its service and manufacturing sectors access to India’s enormous market.

According to ET, Australia, which is quickly becoming a significant partner of India in the Indo-Pacific region, wants to go beyond security and defence cooperation and is in negotiations with New Delhi to establish a trade partner to help the country’s mining industry and wine sales recover from a trade war with China.

Current Australia-India bilateral trade

| Trade ( US $ Billion) | Goods | Services | Total |

| India’s Exports to Australia | 6.9 | 3.6 | 10.5 |

| India’s Imports from Australia | 15.1 | 1.9 | 17.0 |

| Total | 22.0 | 5.5 | 27.5 |

| Deficit(-)/Surplus(+) | -8.2 | +1.7 | -6.5 |

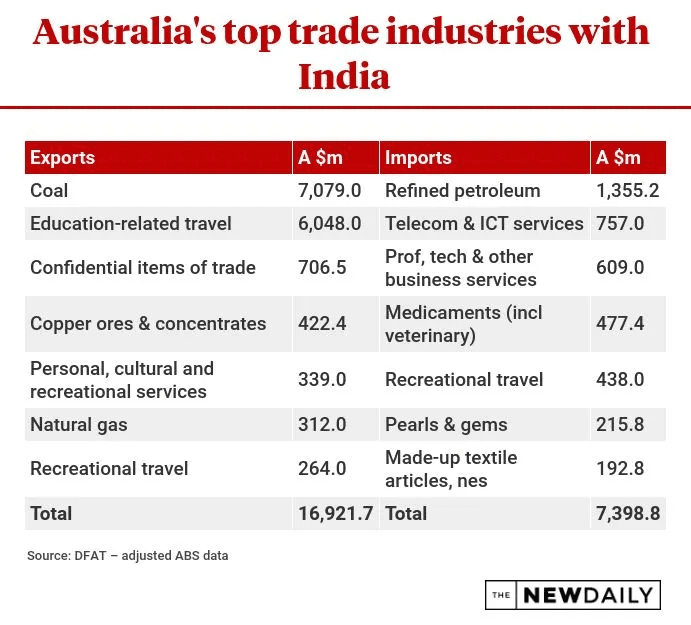

India’s current 17th-largest trading partner is Australia, and Australia’s current 9th-largest trading partner is India. In 2021, bilateral commerce in goods between India and Australia in goods and services was worth US$ 27.5 billion. India’s exports of goods to Australia increased by 135% between 2019 and 2021. India exported goods of US$ 6.9 billion in 2021, the majority of which were completed goods.

In 2021, India imported commodities from Australia worth approximately $15.1 billion, primarily in the form of raw materials, minerals, and intermediate products. Coal makes up three-fourths of Australia’s total imports to India.

While India and Australia have a surplus in their service trade, their merchandise trade is in deficit, primarily because of coal imports.

Why is India not China?

By 2035, India will overtake China as the world’s most populated country and have the third-largest GDP.

The economies of India’s five major cities will be comparable to those of middle-income nations by 2035, and by 2025, one-fifth of the world’s population of working age will reside in India.

Australia’s population is currently 12 times larger than India’s aspirational middle class. All of these figures demonstrate the size of the Indian labour force and consumer market, while the number of people who will have access to the internet is expected to expand to over 850 million by 2030.

Given enormous figures, it is easy to become preoccupied with magnitude and overlook nuances. Even in sectors regarded as traditional strengths, like education and resources, India is still mostly unexplored territory for Australia. Currently, less than 4% of our global two-way commerce is conducted in products and services, with India, lagging far behind China, Japan, and South Korea. India was Australia’s eighth-largest trading partner in 2018–19, with a value of $30.3 billion in two-way goods and services trade. Comparatively, trade with China was worth $235 billion on both sides.

India must be understood on its own terms if we are to increase our trade and investment with it. According to the IES, India is the only nation with the scale to rival China, but it won’t overtake China. The markets of China and India are considerably distinct from one another and are governed by highly varied political, economic, and social systems.

When looking for prospects, it is worthwhile to investigate the high-growth segments of the Indian economy that complement Australian capabilities and characteristics.

India as a key strategic ally

With the challenges of fast urbanisation and infrastructure development, as well as the need to provide resources like clean water, digital connectivity, and health amenities for its expanding and ambitious population, India has emerged as an excellent strategic partner for Australia.

In some crucial areas, such as science, vaccines, pandemic management, space and defence, critical minerals and related technologies, water resources, training and education, the circular economy, waste-to-wealth processes, grain management and logistics, and cyber technologies, India and Australia have excellent prospects for cooperation.

Approximately $20 billion has already been invested by India and Australia into each other’s economies, which is already fueling their trade partnership. This year, bilateral commerce is expected to surpass $27 billion. However, efforts to make conducting business easier and the liberalisation of trade and services will significantly boost this momentum.

What Would an India Trade Agreement Mean for Australian Businesses?

According to experts, the agreement would increase Australia’s trade with India but not fully mitigate the negative impacts of its tense relations with China.

Amid rising diplomatic tensions between Canberra and Beijing, China imposed trade restrictions on more than $20 billion of Australian exports in 2019.

According to recent Treasury estimates, goods like coal, timber, and foods were impacted, costing the affected businesses $5.4 billion in only a single year.

Despite this, a Lowy Institute investigation shows a new trend in local businesses where they swiftly discovered replacement markets for China. India was crucial, especially for the Australian coal producers.

Therefore, a reduction in tariffs on Australian exports to India is good news for industries affected by trade restrictions; but, few experts have asserted that India will never take the place of China in maintaining the country’s terms of trade.

What could India gain in return?

For its development requirements, India requires Australian products including coal, LNG, rare earth, vanadium, lithium, and cobalt. It also needs Australian technology to help with issues like financial inclusion, healthcare, and education.

Of the 49 minerals deemed essential for India’s future strategy, particularly the e-mobility program, 21 have reserves in Australia. The New Education Policy in India has made it possible to work with Australian universities even more frequently. The space and defence industries now have more opportunities for cooperation. India offers a sizable stock of technological resources that suit Australian needs. Opportunities in the infrastructure and toll road sectors are growing for Australian super funds and infrastructure firms.

In addition to securing significant gains in the products sector, India was able to obtain commercially significant offers from Australia in a number of the services industries. The pursuit of a mutual recognition agreement on professional qualifications, post-study work visas for Indian students, an annual quota of 1,800 Indian traditional chefs and yoga teachers entering Australia as contractual service suppliers, and an increased commitment to the movement of professionals as intra-corporate transferees are some of the key gains for Indian service sectors.

Conclusion

The distinguishing characteristic of our region is the resurgence of China and India as significant economies and major powers. Although their trajectories will diverge, the effects of their ascent will be significant.

Neither will progress in a straight line. Because China hasn’t yet reached maturity as a political system and a geopolitical power, its future may be much more unclear. The difficulty for India will be turning promise into success.

Both China and India present Australia with significant potential, and China’s economic expansion has already benefited the Australian economy and may be the single largest factor in the rise in Australian living standards during the past ten years. Although India’s economy is not yet on par with China’s, it is the only one in Asia with the same magnitude, and both countries have a long history of civilisation, which will strengthen their ability to make a wider impact.

Australians are in a good position to benefit from prospects in both China and India. There are huge economic synergies between the two situations. Each diaspora offers a link between the corporate world and the local community. We also face the same difficulties in maintaining the Indo-Pacific region’s strategic stability and economic strength.